KANBrief A European perspective

Technology used by firefighters has traditionally been geared primarily to dimensions of the male body. Design guidelines often lack consideration for the female body. Furthermore, the anthropometric data used as a reference for design is often obsolete.

Technology designed for end users is usually geared – at least implicitly – primarily to male users. A major reason for this is that many products are designed and tested against a standardized adult male (currently 1.75 m in height and 79 kg in weight according to DIN 33402-21, and in many standards only 75 kg).

Awareness of these deficiencies has grown in recent years. The International Standards Organization (ISO) is currently working on a draft standard that will enable all relevant standards to be reviewed in the future for gender equality, and developed further if required2. The body measurements currently in use, which are often outdated, are also being scrutinized.

In a study conducted on behalf of the European Commission and published in 2024, 2,650 harmonized European standards of relevance to occupational safety and health were reviewed to determine whether they give consideration to anthropometric data, and if so to what extent. Such data is relevant in 36% of the standards examined, but is often not given sufficient consideration, or is outdated. For 76 standards, the potential impact of this on safety and health is regarded as high. Some harmonized standards contain up-to-date measurements, but in many cases only for men.

Safety and gender equality in protective clothing for firefighters

The example of protective clothing for female firefighters illustrates the consequences of technology not being adequately designed for both sexes. In an interview study, over 1,700 firefighters, male and female, were asked about the comfort and fit of their personal protective equipment (PPE). Female firefighters in the study encountered poorer conditions and felt less well protected than their male colleagues: the clothing fits them less well, for example because jackets do not close over the hips and trousers are too wide at the waist, too tight on the legs or too long overall (see images below).

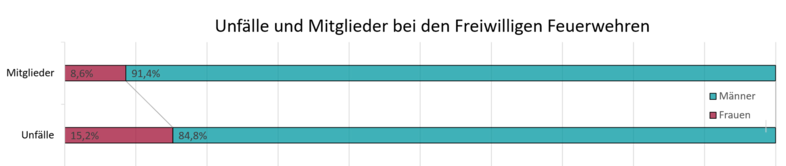

Another study evaluated accident reports from vounteer fire brigades. In fact, the study showed the accident risk for female firefighters to be over twice (205.7%) that for their male colleagues, and that the accidents they suffer are also more serious. This is at least partly due to PPE and work equipment that is poorly tailored to women.

One reason for this poorer protection is that firefighters’ protective clothing is designed primarily for men, who constitute the majority of users, despite legislation and standards requiring clothing sizes to be suitable for a wide user base. Whilst specifying performance requirements for the protective functions, technical standards do not specify manufacturing dimensions. Manufacturers are responsible for taking both men and women into account when designing clothing. This is also clear from the provisions concerning room to move within the clothing and wearer comfort set out in EN ISO 13688, Protective clothing – General requirements.

At the same time, the manufacturing and testing specifications for firefighters’ protective clothing (HuPF)3 adopted by Germany’s conference of ministers for the interior (IMK) set out a minimum standard for manufacturing dimensions. However, these dimensions are intended almost exclusively for male wearers. Manufacturers may deviate from these specifications, but are then responsible for ensuring that safety continues to be guaranteed.

Germany’s HuPF regulations3 require observance of the European EN 469 standard, Performance requirements for protective clothing for firefighting activities. This has both advantages and drawbacks. Protective clothing for firefighters is a product with a guaranteed minimum quality and standardized product characteristics, which permits ready comparison between products at the procurement stage. At the same time, being closely regulated, it is also a product that cannot be developed further without great expense and a substantial business risk.

Creating framework conditions for greater flexibility

Manufacturers may presume that if they observe the harmonized standard, the essential requirements of the relevant European legislation for the design of a product will be met. However, if requirements formulated in harmonized standards are incomplete or outdated – for example because, with a height of 1810±60 mm, the dummies used for testing heat-protective clothing4 are closer in their dimensions to males than females – a risk exists of products being designed that are potentially dangerous for users, even though they comply with the standard.

It is essential that standards and regulations be kept up to date with changes in underlying conditions, particularly body dimensions. Where measurements are explicitly specified, women’s measurements must also be included in the requirements. Any permissible deviations must also be clearly highlighted. This will enable manufacturers to develop technology that is up to date, and users to better evaluate the products available on the market and demand adequate, modern products that are suitable for a diverse range of end users. It will also make it considerably easier for employers to meet their obligation to provide personal protective equipment that is tailored to each and every employee.

Carsten Schiffer, M. Sc.

c.schiffer@iaw.rwth-aachen.de

Professor Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. medic. Dipl.-Inform. Alexander Mertens

a.mertens@iaw.rwth-aachen.de

1 DIN 33402-2:2020-12, Ergonomics – Human body dimensions – Part 2: Values

2 ISO/FDIS 53800, Guidelines for the promotion and implementation of gender equality and women's empowerment

3 Innenministerkonferenz (2020), Herstellungs- und Prüfungsbeschreibung für eine universelle Feuerwehrschutzbekleidung, Parts 1 to 4

4 EN ISO 13506-1:2017-12, Protective clothing against heat and flame – Part 1: Test method for complete garments – Measurement of transferred energy using an instrumented manikin

Source: https://doi.org/10.18154/RWTH-2023-02080 / www.feuerwehrverband.de/presse/statistik